We’re taught that silence is golden, which in some situations it truly is, however for some children, silence is becoming the norm. With the inability to express their thoughts, feelings and opinions with confidence, too many children are locked in semi-silence. The education community needs to act to prioritise the teaching and learning of Oracy, so that all children develop their own voice.

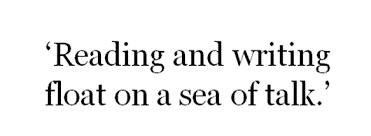

Britton, J. (1983). Writing and the story of the world. In B. M. Kroll & C. G. Wells (Eds.), Explorations in the development of writing: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 3–30). New York, NY: Wiley.

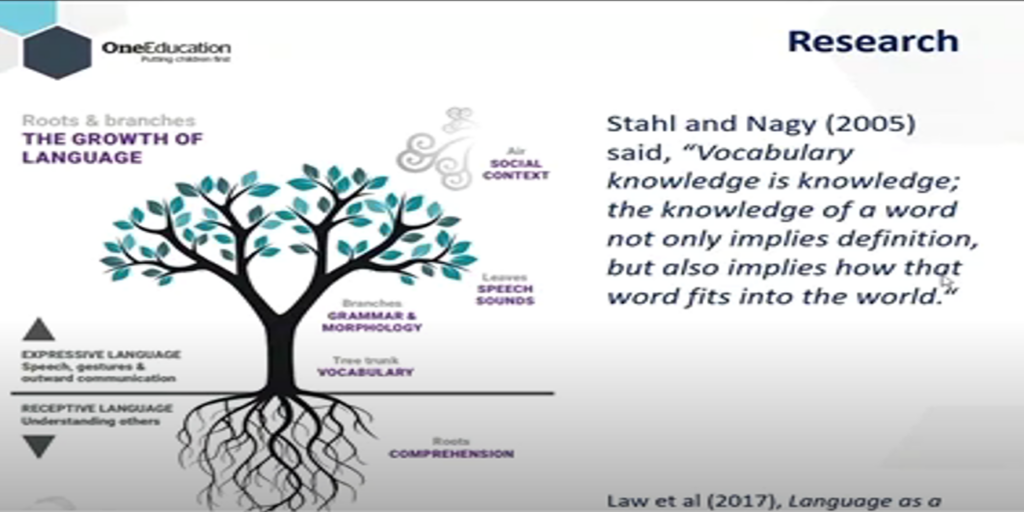

In his much used quote, Britton hits the nail on the head when it comes to the importance of Oracy. Oracy underpins the whole curriculum. But what is Oracy?

What is Oracy?

The term ‘oracy’ was first coined in 1965 by a group of researchers at the University of Birmingham led by Andrew Wilkinson. Developed to describe the speaking and listening skills needed to be a good communicator, it was intended to give spoken language the same importance as ‘literacy’ does to reading and writing. As the English Speaking Union says simply on their website, “In short, it’s nothing more than being able to express yourself well. It’s about having the vocabulary to say what you want to say and the ability to structure your thoughts so that they make sense to others.”

Why is Oracy so important?

We can all understand the importance of being able to communicate with one another. Communication is a key life skill. What happens, then, when your oracy development is stifled? There is a wide body of research which shows that lower levels of Oracy directly impact children’s life chances.

The Communication Trust’s 2017 report, Talking About a Generation found that children who struggle with language or have poor vocabulary at age five are:

- Six times less likely to reach the expected standard in English at age 11 than children who had good language skills at five.

- Ten times less likely to achieve the expected level in Maths.

- More than twice as likely to be unemployed at age 34 as children with good vocabulary.

- Twice as likely to have mental health difficulties, even after taking account of a range of other factors that might have played a part.

The impact of Oracy is clear. Schools aim to prepare children for life and without good oracy skills children will be at a disadvantage. We must give Oracy the attention it deserves.

What do we need to teach?

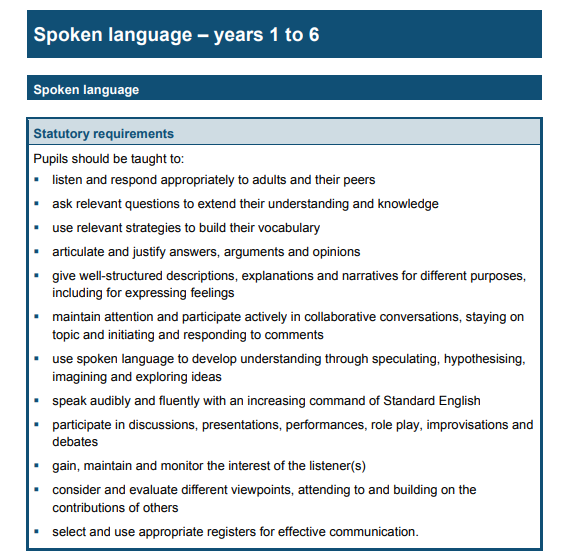

In statutory terms, the Spoken Language elements of the National Curriculum (2014) outline expectations for the teaching of Oracy.

The National Curriculum, Department for Education, 2014.

The National Curriculum, Department for Education, 2014.

Aside from the statutory objectives of the National Curriculum, it is important to also teach children other aspects of Oracy. Children need to be taught:

- The ‘rules’ of social interaction – taking turns; identifying who is holding the conversation and how to judge when this can change; how pairs of language work, e.g. Q and A, greeting and response; how to fix what we say or what we don’t understand.

- Non-verbal cues – voice; volume; intonation; eye contact; pitch; pauses; pronunciation; posture; personal space.

- How to listen.

- How to speak.

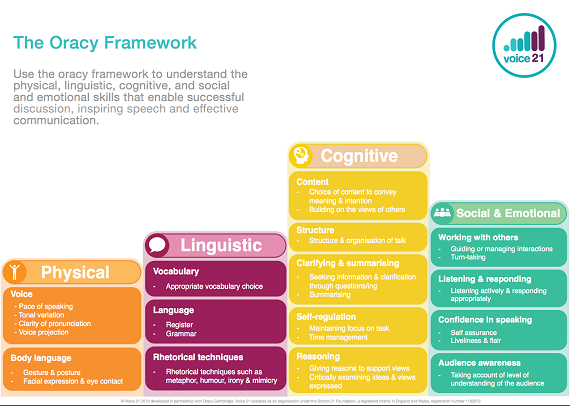

A number of organisations have developed resources that explore curriculums for oracy, including Voice 21, whose Oracy framework is depicted here:

The Oracy Framework, Voice 21.

The Oracy Framework, Voice 21.

The Communication Trust’s Universally Speaking documents are also useful as they break down Oracy development into clear age related expectations.

Our FREE Oracy progression for both EYFS and Stages 1-6 (KS1 and KS2) can be found here:

Despite the fact that Spoken Language forms one third of the English curriculum, its teaching in schools has often been neglected. Too often, Oracy is seen as an activity to support other subjects. Whilst Oracy is important for facilitating learning across the whole curriculum, we must also think carefully about how to teach Oracy itself.

What can we do to improve Oracy?

There are a number of steps schools can take to improve Oracy:

1. Make time for Oracy: Time is needed above all else. Although timetables are already filled to the brim, think about where there might be chances to teach Oracy. You may be able to find time to teach Oracy explicitly as a standalone lesson, however even if you plan in opportunities for oracy into other curriculum areas, this will make a difference. Above all else, do not be afraid to make oracy a focus or objective for a lesson – it is part of the curriculum and needs to be taught.

2. Prioritise Oracy in your environment: Think about whether Oracy is celebrated in your environment. Are children’s verbal comments collected and displayed? How often do you read aloud to your class and tell stories? How many chances do children get to perform poetry and plays? Do you display unusual objects and encourage children to talk about them? Could you have a ‘box of wonder’ in your class to provoke discussion? Could you develop a ‘talking corner’ or invite guests in to talk with, rather than just to, your class? One of our wonderful Reading Award schools, St Matthew’s Catholic Primary School in Bradford, have worked hard over the last few years to develop Oracy. A key facet of their approach is the introduction of ‘talking corners’ into their EYFS classrooms. The idea is simple – each week a guest comes into the classroom and starts doing something they enjoy in the talking corner. Previous guests have brought sewing to complete, or their dancing attire. The objective is for children to be intrigued and spend time talking with the guest, building their oracy skills and confidence.

3. Teach Oracy explicitly: Plan in an oracy focus each week for your class which can be interwoven into your teaching of other subjects. Make time to explicitly teach and model using that focus, giving children chance to try it out for themselves. An excellent place to start with this is by teaching a speaking frame or language structure each week. The wonderful Progression in Language Structures by the Tower Hamlets EMA team provides a clear progression of language structures divided by focus and year group.

4. Give opportunities to practise Oracy: Children need as many opportunities to use their oracy skills as possible. Think about the amount of time you give children for discussion and the structures you use – can you change your approach to encourage Oracy? When you talk with children, do you always question or do you comment and prompt? Do you build upon what children say? For example, if a child says ‘The sponge soaked up the water_’ could you respond ‘_Yes, the sponge absorbed it.’ Think about how often children are given opportunities to report orally, both planned (e.g. presenting research) and unplanned (e.g. How did your group find that?). Could you make time for children to report the day’s news, or show and tell? How can you prioritise conversations with and between pupils and visitors? Could you use roleplay? Or have a ‘conversation station’ with prompts to promote conversations between children?

5. Have high expectations for Oracy from all: Being a good role model for Oracy is crucial. Just as using your thinking voice is an important tool for developing children’s metacognitive skills in Writing, so it is for Oracy. Verbalising making oracy choices and thinking about the most effective way to phrase speech is key to supporting development. Feedback about Oracy is also helpful. If a child says something incorrectly, rather than focusing on their mistake, repeat what they said back to them using the correct phrasing. For example, if a child asks ‘Can I toilet?’ say ‘_Please can I go to the toile_t?’ back. Where possible, praise and give feedback on speech specifically, even when oracy is not necessarily your objective or main focus. For example, ‘I think the way you explained that had a really clear sequence.’

6. Have fun with Oracy: Enjoy debates, performances, role play and games together, where Oracy takes centre stage. A whole range of ideas can be found on our webinar recording discussed below.

For more information on our training and other support available for Vocabulary and Oracy teaching, please email laura.lodge@oneeducation.co.uk