With the new series of the Great British Bake off about to begin, it’s not only cakes and biscuits we can learn from the new bakers but metacognition theory as well.

Initially, talking about metacognition in the classroom can on the surface appear very ‘meta’. Just another on-trend phrase, ready to throw into a conversation in order to appear “well-read” and up to date with the latest evidence-based practices.

However, how can this word really help us to adapt our practice to ensure our children have the best possible learning experience in our classrooms? The simplified definition often describes metacognition as ‘thinking about thinking’ – which in itself is a wonderful phrase, yet what does it mean when we picture 30 little faces staring back at us?

Metacognition helps learners make strategic decisions while engaging in a task and, as a result, adapt their behaviour and thought processes to help them achieve the intended goal.

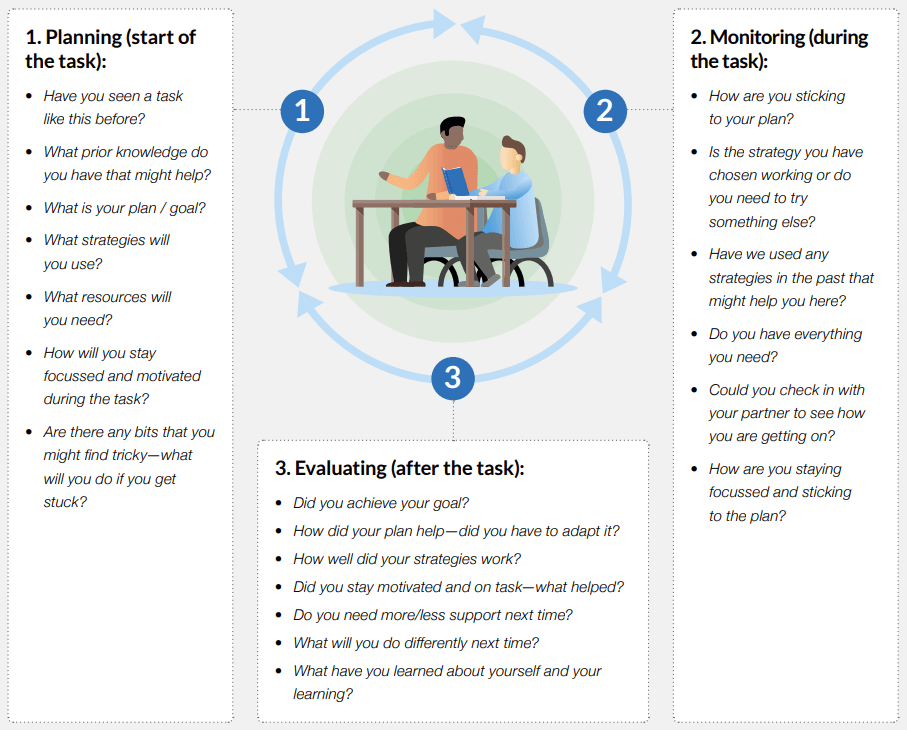

The Education Endowment Fund (EEF) have broken it down into 3 more manageable areas to think about in learning:

“It is about planning how to undertake a task, then cognitively undertaking that activity, while monitoring the strategy to check progress, then evaluating the overall success.”

Therefore, as teachers, we should consider how we structure and deliver our lessons using these 3 key areas. For some children, this process will come much more naturally. On the flip side, there are also many children for whom these thought processes for metacognition do not come as easily. This means we need to plan for explicit teaching of the methods in order for all children to succeed.

The Bake Off and the dreaded “Technical Challenge”…

For avid viewers of the bake off, they’ll know that each week the contestants dread the upcoming technical challenge. A challenge designed to test the baker’s core knowledge and skills in a variety of baking disciplines. Bakers are given a pared-back recipe or, sometimes, a completely unknown recipe, which they are asked to bake according to the limited guidance. We then watch the bakers as they question the recipe, draw on prior knowledge, and adapt their plan as they go in order to have a finished baked good by the end of the allotted time period.

But how does this link to using metacognition?

Throughout this challenge, we see the three stages of metacognitive reflection:

- Planning

‘I’ve made a similar cake and so I’ll just apply the same method for combining all these ingredients together.’

‘I think I need to warm the butter up first so that it all combines smoothly.’

‘Hmm, I know it normally takes me a while for these types of cakes to bake, so I need to give myself plenty of time to get it in the oven’.

- Monitoring

‘Am I on the right track?’

‘Do I need to adjust my oven temperature to ensure it’s baked all the way through?’

‘Should I use the technique everyone else seems to be using or stick to my original plan?’

- Evaluation

‘How did I do?’

‘Did I use the right method?’

‘What would I do differently if I had another go?’

During the challenge, we can see that the bakers apply metacognitive approaches throughout. They are able to do so using a foundation of strong subject knowledge (cognitive strategies), which they are able to draw upon to think about the task on a deeper level and consider how they can break it down so that they can achieve a finished bake.

As teachers, we can reflect on the following: how easily can our children can draw on the metacognitive strategies to further support their learning? If we could hear the children’s internal voice, how many would instinctively know to draw upon prior learning to help them solve a maths problem, how many might ask a variety of monitoring questions when faced with a challenge?

In years gone by, we might have simply said the phrase ‘3 before me’ when the children face a challenge. This means before asking the teacher a question, children are reminded to think carefully about it, look in their book, or ask a friend. However, if the children lack the monitoring questions required when facing a challenge, then neither their friend nor their own mind will be able to support this process. Therefore, support for the child only ever comes from an external source – the teacher. With class sizes of often 30+, that’s an awfully large number to support in one lesson.

Yet, if we can teach the children how to apply the metacognitive strategies the bakers demonstrate, this would lead to greater outcomes from the children. They will become more effective and strategic learners that are able to not only hold knowledge, but to draw on it in many ways, connecting the sources and starting the transition from novice to expert.

What can we do?

Simplistically, we make the invisible, visible. That invisible thinking process is often seen as a complex web however, as experts in our field, we can help explicitly teach the process, demystifying the unknown. We begin by teaching the metacognitive strategies as endorsed by the EEF of helping children to plan, monitor, and evaluate.

The EEF provide a general overview which is seen below:

What it key is that rather than ask generic questions, we adapt these to suit the purpose of the lesson and so that all questioning becomes relevant to the day’s specific task. In order to achieve success, this is a process that will take time to embed and will require teacher modelling of the thought processes, with scaffolding included, so that over time this shift in thinking becomes habitual.

Our support

The process can seem overwhelming, so where to begin?

Use our free ‘Sample Metacognitive Questioning Audit’ to start with to help review current practice and begin the journey of developing metacognition in your school.

For more support, please get in touch with our School Development team. Our experts can cover the following areas:

- Applying the Seven Step Model more discretely to the school setting thinking about tailoring the CPD to the school’s needs.

- Reviewing the use of modelling in schools thinking about how this includes the principles of metacognition.

- Challenge within the curriculum. Challenge within classes is key to ensuring the Goldilocks effect (not too easy, not too hard) which unlocks the potential of metacognition.

- Developing metacognition through the use of talk in the classroom.

For more information on Metacognition and how we can help support your school, please contact Liz Dwarampudi, Education Consultant at liz.dwarampudi@oneeducation.co.uk

Please complete the form below and we will get in contact as soon as we can to help you with your query.