As adults, we often forget what it means to read as it has become automatic to many of us – but reading can be complex. For children, who are not yet automatic readers, we must consider how best to teach them the literacy skills and strategies of being a fluent reader.

Our previous blog in this series focused on the teaching of retrieval in reading, but the reading skill that children often find most challenging after this is inference.

What is inference?

We all use inference daily in many different scenarios, often determining a person’s mood or emotions based on their posture or facial expression. We can also make inferences on their preferences by the clothes they wear, food they eat and music they listen to.

Essentially, inference is the ability to make an educated assumption about a specific scenario – in the context of this blog, the scenario is a scene or plot within a book or extract.

Inference is an essential skill to help us understand the world in which we live and we all have an innate ability to infer. However, making inferences is not always clear cut, especially when reading.

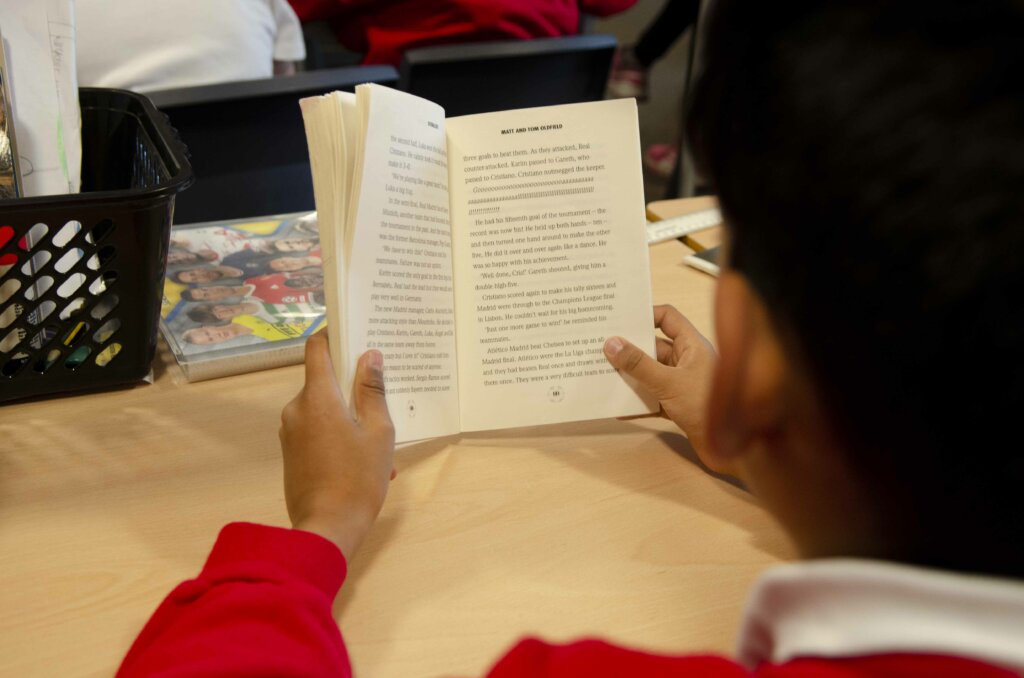

To become a really confident reader, we must teach children how to infer and give them as many opportunities as possible to read and make inferences. But in order to teach inference, we need to ensure they have sufficient subject knowledge.

Examples of inference in reading

When people talk about ‘inference’ they often refer to the expression ‘reading between the lines’, but what does this actually mean? Anne Kispal explains that it suggests:

”When authors write, they do not describe every detail of events, characters’ feelings or their motives. There are often ‘gaps’ in the narrative, requiring the reader to comprehend or ‘work out’ the implication, instead of being provided with every specific detail.” – Anne Kispal, Effective Teaching of Inference Skills for Reading

It is this technique which makes their writing interesting, requiring the reader to use their imagination and raising the level of reading enjoyment. An author will expect the reader to use information from the text to arrive at other implied information or conclusions.

Take these sentences:

Maggie loves to play catch. She especially loves playing catch in the park but sometimes Laura has to help her find the ball.

If we only retrieve the words on the page, we miss half the meaning – we know there is something called Maggie and something called Laura. We know Maggie loves to play catch but Laura has to help her find the ball.

However, when we infer, we fill in these gaps. We can infer that Maggie is female, that Laura is in a caring role and that Laura is probably female too. If we have the requisite background knowledge, we might also infer that Maggie is a dog! By using inference, we put the flesh on the bones of writing, but inference is not an easy skill to master.

Kispal’s literature review demonstrates that inference can be split into a number of different categories. However, there are two commonly used categories that most researchers agree with.

Coherence inferences

Necessary for basic comprehension, these types of inferences can be created from an understanding of the text’s cohesive devices, such as pronouns or from making very simple links to background knowledge of the text. Coherence inferences are the inference skill that we use most when reading.

For example:

Maggie loves to play catch. She especially loves playing catch in the park but sometimes Laura has to help her find the ball.

The reader needs to understand that the pronoun ‘she’ is referring to Maggie (use of cohesive devices) and that Maggie loves playing catch in the park. These two pieces of information are essential to be able to construct meaning. These inferences are easier to make as they require very little background knowledge.

Elaborative inferences

These types of inferences are not necessary to basic comprehension; however, they do give us more information and make a text more interesting by enhancing or intensifying details.

An elaborative inference could be about the consequences of an action, a prediction or speculation. Elaborative inferences depend on background knowledge and therefore are often more challenging than coherence inferences.

For example:

Laura was walking through the empty forest. Suddenly, she heard footsteps. The world went black.

The reader needs to use their background knowledge to understand what might be happening and elaborate on the situation. They may use their own experiences of walking through a forest alone, or their prior reading of mystery/suspense texts to fill in the gaps.

Children even need to understand the fact that an empty forest would still have trees. Making these elaborative inferences depends on the reader’s background knowledge.

How can we teach inference effectively?

Build background knowledge

Background knowledge, life experience and cultural capital drastically impact inference. Bowyer-Crane and Snowling (2005) found that children’s ability to comprehend the meaning of a text or read it fluently will be negatively affected if their general knowledge cannot assist them in reaching a conclusion. Without the necessary background knowledge, children will struggle to make inferences despite high-quality teaching of the skill.

Consider a traditional tale such as Hansel and Gretel. Children cannot make inferences about the witch’s motives if they do not know what a witch is and how they often behave in children’s fiction.

If a child does not know how delicious gingerbread is, they will not be able to make inferences about why the witch has built the house like that.

Crucially, when the witch is pushed into the oven at the end of the story, without background knowledge about fairy tale endings and even ovens, children are unlikely to infer that the witch is actually being killed, therefore missing a crucial part of the meaning!

It is important to build opportunities for background knowledge development into your reading teaching sequence, to provide children with the foundational knowledge they need to be able to understand the text deeply and be able to make inferences whilst reading and during book talk.

Our Reading Gems teaching sequence for reading, builds in both background knowledge development and vocabulary building prior to reading to support just that.

Teach and model the skill in action

It is important to explore what inference is and explicitly model close reading and how to make inferences from different texts and situations. This will usually be from a text but can also be from another source – inferences can be made from facial expressions, clothing, possessions and even shopping lists!

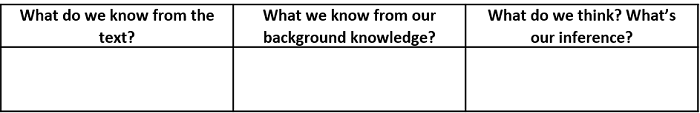

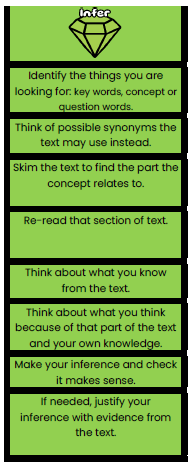

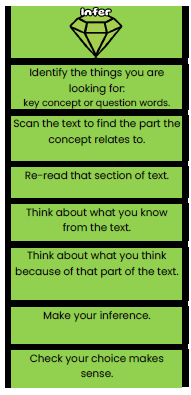

When teaching inference, your modelling of your thought process is crucial. Children need to understand that when they make an inference, they are combining what they read with what they know. Our skills ladders can be used to support modelling and children’s thinking when making inferences, or you may also wish to use a graphic organiser to support discussion.

Give children opportunities to practise and apply

Work with children to make inferences in different contexts, using a range of texts, including across the wider curriculum. You could explore activities such as:

Where am I and what am I doing?

Share a sentence such as:

My hair’s whipping in my face, salty crystals collecting on each strand, whilst I look towards the horizon.

What can children infer about where the character is and what they are doing? What might the character be thinking?

Me tubs

Fill a tub with objects that sum up aspects of your character, or a character from the text you’re reading. What inferences can children make from the objects? Can they match tubs to characters? Can they explain their reasoning?

Six word stories

Share some examples of six word stories with children. For example:

Sorry soldier, shoes sold in pairs.

Explore the story together – what inferences can children make about the character and their background? What do you think is happening in this scenario

More examples are available on Six Word Stories

Thought clouds and speech bubbles

Use images alongside text to make inferences about a character’s thoughts and feelings at key points in the text. Challenge children to fill thought clouds and speech bubbles with characters’ reactions, using the text to inform their reasoning.

Crime scene investigations

Conduct a crime scene investigation in your classroom. Can children take clues from the scene and infer what has happened, the identity of the victim and whodunnit?

Once children are ready, provide opportunities for them to make inferences independently from a wide range of sources. This may be through questioning or it could be through activities like the ones above.

By building in as many opportunities to make inferences, and discuss their reasoning, as possible, you’ll be giving them the best chance to become confident with this most crucial skill.

Further literacy support with One Education – improve reading comprehension

Supporting children to develop their reading skills is a crucial part of reading teaching. Our literacy training explores how to teach each of the key reading skills in detail.

For more information on how we can improve the literacy teaching skills in your school, contact us.