‘Children, we know, need to talk and to experience a rich diet of spoken language, in order to think and to learn. Reading, writing and number may be the acknowledged curriculum ‘basics’ but talk is arguably the true foundation of learning.’

Improving Oracy and Classroom Talk in English Schools: Achievements and Challenges, Robin Alexander (2004)

We know oracy to be a key life skill; a competence that offers opportunity beyond the confines of the curriculum and which contributes to wellbeing, improved academic outcomes and relationships. Labour’s pledge is that the forthcoming revised curriculum will recognise the centrality of oracy for learning to ensure schools establish effective oracy practice for the improvement of their pupils’ future life chances. But before the Curriculum and Assessment Review findings are published, what can schools do to develop their oracy provision further? What can excellent practice in oracy look like?

When considering how to progress oracy provision in school, there must be a holistic approach. A useful model is that created by the Oracy Education Commission: Learning to Talk, Learning through Talk and Learning about Talk.

We Need to Talk, Oracy Education Commission (2024)

Learning to Talk

‘Oracy is an outcome of learning, whereby pupils learn to talk confidently and appropriately in a range of different contexts. It is also a process of learning, where learning through talk deepens pupils’ understanding through interacting with teachers and peers.’

Alexander, R. (2008) Towards Dialogic Teaching. Rethinking Classroom Talk.

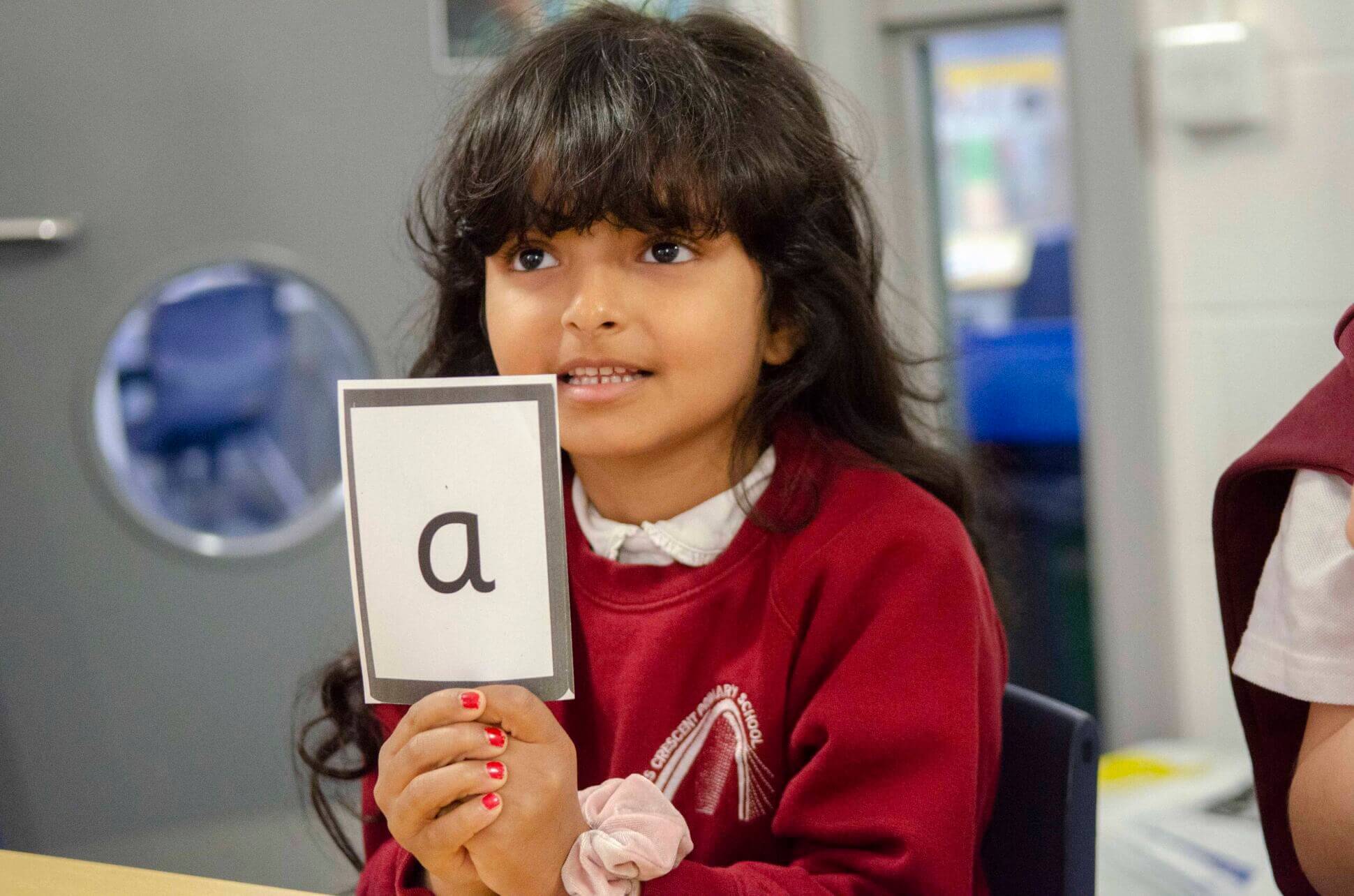

Oracy needs to be regarded as a curriculum goal in its own right, not just as a by-product of other learning. Teaching children how to talk and communicate effectively is fundamental to their success. Just as we explicitly teach reading and writing, we must also teach speaking and listening skills with the same level of importance and structure.

Developing pupils’ ability to talk with confidence and clarity requires more than just exposure to spoken language—it demands deliberate teaching, modelling, and structured opportunities to practise. Teachers play a crucial role in scaffolding pupils’ speech, providing them with the vocabulary, sentence structures, and conversational skills needed to communicate effectively in different contexts.

Although speaking and listening and communication and language are statutory elements of the curriculum, for oracy to have the prominence it deserves, oracy lessons need to become a protected part of the timetable: a way to teach the core elements of talk modes, practices and a school’s rules and expectations for talk. During these dedicated lessons, pupils will have the chance to take part in a range of talk contexts and wider opportunities to not only craft their own skills in speaking and listening, but to deepen their understanding through talk. Moreover, children will develop awareness of the diversity of talk, its history and how this relates to the language they use in each context.

Talking to learn

Alongside the development of talking and listening skills, schools need to provide pupils with further opportunities to talk to learn. This means ensuring that talk is not just a vehicle for communication but a fundamental part of the learning process itself.

‘Humans have a great capacity for learning and, uniquely, a special capacity for learning language. This in turn enables us to learn from, and with, other people. By acquiring language, we become able to not just interact, but to ‘interthink’.’

Littleton, K. & Mercer, N. (2013) Interthinking: Putting Talk to Work.

Giving pupils opportunities to practice and improve their skills in being able to talk clearly and accurately is an obvious foundation, yet how often is this prioritised in the busy curriculum we host? The focus can all too often be on getting through the content, rather than spending time discussing it. Time taken to instil pupils’ talk and listening confidence and competence through enabling high-quality oracy opportunities will provide the foundation required to progress your pupils’ talk skills.

High-quality classroom talk—whether through structured discussion, exploratory talk, or collaborative reasoning—enables pupils to clarify their thinking, deepen their understanding, and engage with complex ideas. Much research into dialogic teaching highlights the value of open-ended questioning, teacher-pupil dialogue, and structured peer discussion as ways to enhance critical thinking and comprehension.

To foster an environment where pupils genuinely learn through talk, teachers must actively model and scaffold effective discussion techniques. Encouraging pupils to build on one another’s ideas, justify their reasoning, challenge constructively, and articulate their thinking strengthens both subject knowledge and oracy skills. By embedding purposeful talk across all subjects, valuing collaborative learning, and ensuring pupils have frequent opportunities for meaningful discussion, schools can transform oracy from an overlooked skill into a cornerstone of educational success.

Indeed, the commission calls for more opportunities for pupils to be assessed through their oral outcomes. Supporting pupils to reflect on the effectiveness of their oral contributions linked to following talk rules, the physical, cognitive, social/emotional and linguistic elements required for the purpose and audience is an effective starting point to enable all pupils to achieve purposeful talk outcomes.

Learning about Talk

‘The things we say and how we say them can inform, influence, inspire and motivate others and express our empathy, understanding and creativity. It is our ability to communicate that enables us to build positive relationships, collaborate for common purpose, deliberate and share our ideas as citizens.’

Beccy Earnshaw & Peter Hyman in Millard, W. & Menzies, L. The State of Speaking in Our Schools (2016).

Finally, we also need to consider how to support pupils to learn about talk. In the past, Received Pronunciation was seen as the ‘correct’ way to speak, with accents and dialects sometimes actively discouraged. Now, as a society we rightly value all forms of talk, but pupils do need to learn about talk in order to do this, and to be able to understand ‘how’ to talk in different situations. Barbara Bleiman sees the following aspects of learning about talk as crucial:

- Key differences between speech and writing

- Debates around spoken standard English

- Hybrid forms such as social media posts, WhatsApp messages, texts

- Sociolinguistics – how speech, including accent, varies according to class, race, geography, gender, age and how it is perceived and valued

- Pragmatics – how context plays a role in meaning-making, how we interpret meaning in subtexts and implicatures

- Conversational features and politeness principles

- Group languages – jargon, specialised or in-group language

- Speech acquisition in children and how that relates to other aspects of language development, including the relationship between first language and second language learning, as well as learning a foreign language.

By teaching pupils explicitly about talk, we not only encourage them to celebrate and value talk, but also understand how different codes of talk are used, and how to code-switch according to need, building, as Hymes (1966) coined, communicative competence over time.

As a sector, we must take proactive steps to embed oracy at the heart of the curriculum, ensuring that pupils not only learn to talk but also learn through and about talk. By protecting time for explicit oracy teaching, fostering high-quality talk interactions, and deepening pupils’ understanding of language diversity and sociolinguistics, schools can empower students with the communication skills they need for success. As we await curriculum reforms, we can drive change by prioritizing meaningful classroom discourse, valuing diverse linguistic backgrounds, and equipping pupils with the tools to navigate different talk contexts.

The One Education Oracy Award

In April we’ll be launching the One Education Oracy Award, a tool designed to support schools from EYFS to Secondary level to develop their Oracy provision. Building on the success of our Reading Award, which has supported hundreds of schools to improve their reading curriculum offer over the last nine years, the Oracy Award will offer research-backed review, development and training to schools who want to ensure all pupils learn to communicate well.

Over the next few months you’ll be hearing more about the One Education Oracy Award and the support we can offer you. Watch this space!

Please complete the form below and we will get in contact as soon as we can to help you with your query.