On the 5th March, OFSTED’s long awaited English subject report was published. It recognises how much work schools have done to improve the quality of teaching and learning in English, but it also emphasises the need for more to be done, particularly with regards to Writing and Oracy.

“While English remains at the heart of the school curriculum and there is much to celebrate, there is more to do if we are to make sure that all pupils achieve well.”

With this in the mind, the report provides several recommendations and examples of practice for schools and leaders to take forward. However, OFSTED have been clear that the recommendations are not a checklist for inspectors, as they recognise that “…there are many different ways that schools can put together and teach a high-quality English curriculum.” Whilst the report is based on the best practice inspectors have seen in schools, it is not exhaustive. Care needs to be taken not to rush in and rip up what is working, but simply to use the report to consider where we may need to go next in some areas of our English curriculums. We will have to wait to see how the report impacts the Education Inspection Framework in the future, but how can we use it to impact best practice now?

In the first of our OFSTED English Subject Report blog series, we are going to focus on the implications for teaching, learning, and leading Writing in primary schools. So, what are our top takeaways from the report?

The Importance of Clear Curriculum Planning

Several of the report’s recommendations focus on curriculum planning and how this translates to the classroom. Whilst schools have worked hard to develop curriculum plans over time, the report offers some important thinking points to consider. One aspect is the way schools choose texts to study, with the report finding that too often, wider curriculum topics are used as the main reason for choosing texts in English. While this is sometimes useful, especially where children are going to be writing using the knowledge they have learned previously in History for example, OFSTED are clear that texts should be chosen primarily for their literary merit. So, in practice, what does this mean? It does not mean necessarily changing the texts you use but reviewing them within your usual monitoring cycle and discussing whether they are supporting children to build understanding of literature and language, not just adding to their curriculum knowledge.

As well as text choices, the report also looks at schools’ choice of writing outcomes. It particularly emphasises the need to focus on building writing fluency and foundational knowledge as a priority before more complex writing is introduced:

“The writing curriculum often introduces complex tasks too early, before many pupils are equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills that underpin these.”

Reviewing your long-term planning with an eye to this is important. For too long, in many schools, curriculum outcomes for writing have been unduly impacted by the perceived need for ‘evidence.’ Thankfully, gone are the days of writing portfolios, but the expectation that children write whole texts from the EYFS is still very much in place in some schools. Considering how soon ‘whole text’ writing begins, how we build up to this and how written composition can be balanced with oral composition is crucial if we are to support children’s development of writing fluency over time.

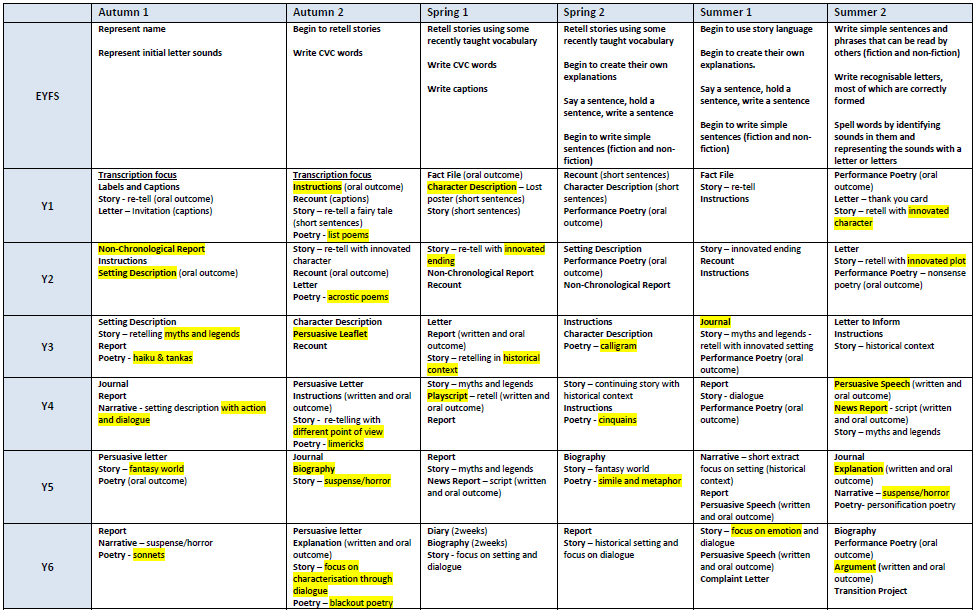

This can be built into a wider conversation about how we sequence the teaching of writing outcomes. How can we build progression but not spread children’s knowledge too thinly? I often ask schools to consider what their children need to be able to write by the time they leave school. Usually, the list of text types that comes out of that conversation looks quite different to those on the school’s long-term plan. Minimising the number and range of text types taught and repeating them over time, can support children to apply their writing knowledge more effectively and gain fluency. An overview of outcomes could look something like this example of Writing Text Type & Genre Progression:

You will note that within each year, and over subsequent years, text types and genres are repeated to support deeper understanding. New or adapted text types and genres are added gradually over time (highlighted in yellow) with some phased out as pupils become more confident writers. Having a smaller range of text types also supports teachers to build deep knowledge of the grammatical features needed, but we need to do more to support teachers than just outline our outcomes. The report explains that schools must:

“…ensure that teachers understand what pupils need to learn to be successful in English and how to teach and assess this help schools to understand the different components of written and spoken language and how to sequence, explicitly teach and assess them.”

One of the examples that OFSTED gives is ensuring plans support staff to “…know how to identify the grammar and vocabulary that pupils need to be taught, and to consider how tone, register and syntax differ, depending on the form chosen.”

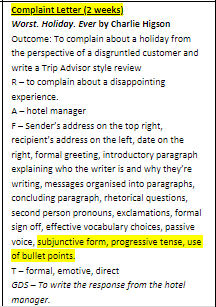

A useful strategy to support this is our R.A.F.T. structure for writing:

This is designed to support staff to interrogate texts and outcomes, guiding discussions all the way through the writing process on how to write effectively. It also acts as a structure for staff to identify the grammar and vocabulary that needs to be taught. Schools we work with are finding it helpful to include R.A.F.T. on their curriculum plans, not just make it a focus within their writing teaching sequence, so that these features are clear for teachers, whilst also supporting progression in English knowledge over time. Here is an example for what that could look like:

Having a clear R.A.F.T. can support staff to understand what to focus teaching on, and guide their exposition of texts with pupils, building their knowledge of being a writer and teaching writing. However, regardless of how clear our curriculum plans are, if we want our teaching to have real impact, we must make sure staff have the knowledge they need to use them effectively, including when to adapt them to suit the needs of their pupils. Building in time to review curriculum plans regularly during the year can also make a positive difference. Having a regular dialogue between the English team and teachers can support staff to become more confident in spending time addressing misconceptions or changing outcomes to suit the needs of their pupils, rather than slavishly sticking to the school’s curriculum plans. This way, curriculum plans become working documents, used actively to support pupils’ outcomes, and address their misconceptions.

Key Questions:

- How are texts chosen to inspire writing? Are they chosen for their literary merit?

- Are opportunities for oral composition (as the end point) built into long term plans?

- How do outcomes progressively challenge pupils? Is there sufficient word and sentence level writing in EYFS, KS1 and beyond to support pupils to build foundational skills?

- How confident are staff with teaching how to write for audience, purpose, and tone, adapting their choice of vocabulary and grammar accordingly?

- How often are curriculum plans reviewed? Who does this? Are curriculum plans used as working documents?

Building Fluency in Transcription

As well as curriculum planning, the report offers several observations about children’s writing fluency and knowledge of transcription. Fluency in transcription is key not only for accurate spelling and clear handwriting, but also for the fact that it lessens the cognitive load of writing. Without fluency, children must focus on the mechanics of writing, rather than being able to consider the craft of writing. Despite its importance, OFSTED notes that,

“Primary pupils are not given sufficient teaching and practice to become fluent with transcription (spelling and handwriting) early enough.”

Considering how spelling, handwriting (and the foundational skills needed for both) are taught in your school is key. Too often, we see children in KS2 struggling to reach the expected standard due to a lack of fluency in transcription, but this is not an easy fix and often requires ‘unlearning’ embedded errors and misconceptions. We need to get the teaching of transcription right from the very start and continue with it as a key focus all the way through children’s time at school.

The teaching of spelling is often thought to begin with Phonics, but it starts before that with children’s foundational knowledge of phonology. Considering how this foundational knowledge is built over time and continues throughout Phonics teaching and beyond is beneficial. Think about the old ‘Phase 1’ of Letters and Sounds and whether your chosen SSP scheme teaches those foundational skills. Whilst the report acknowledges the excellent work schools have put into the teaching of Phonics and the benefits that are being reaped from this, it does note that the lack of Phonics training for KS2 staff prevents Phonics learning from having the impact it could on spelling further up the school.

Most schools now teach spelling from a scheme, often one linked to their chosen SSP programme. Whilst this provides consistency and structure, it is still important to review how effective it is, how consistently it is being implemented and the impact it is having on children’s spelling knowledge. One area to consider is whether it supports teachers to address gaps in previous learning. If not, timetabling in additional time to teach missing spelling knowledge is key. However, time needs to be taken first to assess children’s specific gaps, through analysing their independent writing and completing diagnostic assessments. We have developed dictation exercises, matched to the National Curriculum, to support the teaching and assessment of spelling, an example of which is available for download here. These resources can also be used as practise dictation exercises which can, as the report notes, support the development of fluency in both spelling and handwriting.

Whilst spelling teaching is on the way to becoming much more consistent, the teaching of handwriting has seen less focus in some schools. In some settings, handwriting is rarely explicitly taught, particularly once children reach KS2, and often relegated to morning work. Whilst time to practise is important, children need explicit teaching all the way through school to ensure correct letter formation and to build fluency. Underpinning this is a need for strong motor skills teaching from the EYFS, which continues as long as children need it, as without this, handwriting fluency is impossible. Reviewing your school approach to the teaching of handwriting from the EYFS upwards is key. Whether you choose to invest in a scheme or not, the National Handwriting Association has a range of free resources to help build consistency in your handwriting teaching.

Key Questions:

- How is spelling taught in school? Is dictation used? What impact is spelling teaching having?

- How are gaps in spelling knowledge filled over time? How are children identified as needing intervention and what does this look like?

- How is handwriting taught in school? What impact is it having?

- How are fine and gross motor skills developed over a child’s school journey? How are children identified as needing intervention and what does this look like?

Applying Grammar and Punctuation Knowledge

The report builds on its exploration of fluency to discuss pupils’ overall grammar and punctuation knowledge, finding that:

“Schools teach grammar, sentence structure and punctuation explicitly. However, pupils do not always get enough practice to secure this knowledge. For example, oral composition is rarely used to practise using grammatical conventions and different sentence structures.”

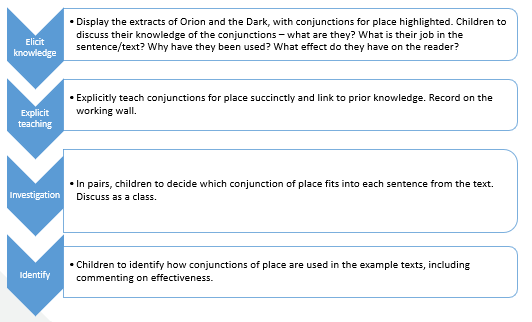

Although the teaching of grammar, punctuation and sentence structure has moved on since the introduction of the GPaS tests in 2016, in many schools the focus is still on decontextualised grammar teaching. In practice, this supports test technique, but has little impact on children’s writing, or understanding of being a writer. As the report warns, it is important not to allow the content of assessments to dictate the curriculum, and with GPaS this is crucial. For grammar teaching to have real impact, we need to consider how to provide children with multiple opportunities to engage with grammar, both in writing and oracy, in the lead up to drafting.

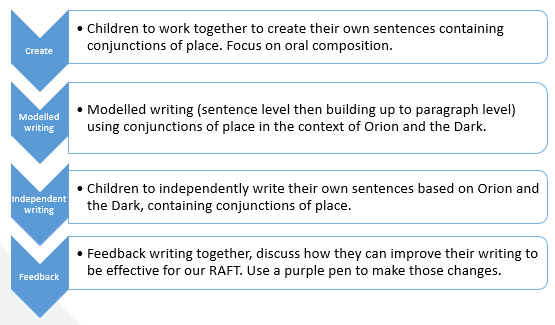

Having a sequence for the teaching of grammar and punctuation can be helpful to address this. At One Education, we have developed our own structure which incorporates explicit teaching, practise, and application, to really support children to understand how to use their knowledge in their writing. Here is an example of our sequence, with thanks to Chapel Street Primary School:

Having a clear grammar sequence is just the start, and care needs to be taken to continue the discussion of grammatical knowledge all the way through teaching, drafting, and editing for it to have a real impact. Using the R.A.F.T. structure or exploring audience and purpose in your own way supports this, providing the opportunity to engage children regularly in conversations about how their grammatical choices affect their reader, support their purpose for writing and reflect their tone. This way, grammatical knowledge is not pigeon-holed into a game of feature spotting, but instead used actively as a writer’s tool.

The report also recommends that schools consider how children’s errors are addressed, saying in many schools “Pupils’ books show that fundamental errors go unnoticed and persist over time.” Having a clear feedback policy is important, focusing feedback on the most important foundational knowledge first. However, the real key is to ensure feedback leads to pupils’ errors and misconceptions being addressed in a timely manner, not just pupils having their mistakes corrected. Planning in proofreading time to every lesson (even outside English) is a fantastic way to provide some focused teaching unpicking misconceptions, whilst giving children the chance to learn, through modelling, how to use this important skill and address the root cause of their errors, avoiding them becoming embedded over time.

Key Questions:

- How do children practise using grammar and punctuation knowledge that is taught? Are there opportunities built in for oral composition? What about word and sentence level writing?

- How are errors in children’s writing identified and how are misconceptions addressed? Do children have the chance to regularly proofread their writing? What does this look like?

To unpick more of the detail behind the report and really delve into how to implement the recommendations in a sustainable way, we are running a virtual training session on 30th April, ‘Telling Your Story: OFSTED’s English Subject Report and Your School’. For more information or to book a place for only £45 please click here to visit our website.

If you would like to discuss how One Education can support you to review and develop your English curriculum please contact our Literacy Team Leader, Laura Buczko at laura.buczko@oneeducation.co.uk. Look out for the next blog in our OFSTED English Subject Report series, focused on the report’s implications for teaching and leading Oracy, coming soon!

Please complete the form below and we will get in contact as soon as we can to help you with your query.