Breadth, depth and frequency of reading matter

Reading Framework, 2023.

The Reading Framework, first published by the DfE in July 2021, has been fundamental when schools have been considering the teaching of Early Reading (read our summary here). This month’s update sees the guidance extended to include more information for KS2 and also pupils in KS3, up to the age of 14. Oracy and developing vocabulary continue to underpin the guidance; the best way we can develop the children as readers is to immerse them in language and model literacy skills throughout their learning journey. This links directly to cultural capital, ensuring high quality input and thus the best possible start for all children.

The recent PIRLS data shows that pupils in England are ranking more highly than ever amongst the 44 nations participating in the study. Despite this recent success, it is important to note that the attainment gap between pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds and their peers continues to widen. The impact of being a confident and capable reader lasts long after pupils leave secondary school; it stays with them for life and opens opportunities that they otherwise wouldn’t have had.

With this in mind, let’s now look at our top takeaways from the recent updates to the Reading Framework, and how we can use this in our practice to help all children leave school as readers.

DEVELOPING FLUENCY

“As pupils gain fluency, their motivation increases: they start to enjoy reading more and are willing to do more of it.”

As children move through the school into KS2 and beyond, the expectation is that once they have acquired phonics, they are fluent – this is not the case and an area of learning we need to continue to model and teach. It is helpful to view fluency as progressive; it takes continuous practice as the texts become more challenging.

The EEF’s ‘Improving Literacy at KS2’ defines reading fluency is defined as reading with:

- accuracy (reading words correctly);

- automaticity (reading words at an appropriate speed without great effort); and

- prosody (appropriate stress and intonation).

Dr Tim Rasinski describes fluency as ‘a bridge between effortful decoding and comprehension’; reading with sufficient ease so that pupils can focus on the meaning of the text. The Reading Framework updates include strategies to support fluency once children can decode, for example echo and choral reading, and highlights the importance of modelled reading aloud across the curriculum, repeated reading of a text and opportunities for the pupils to read aloud.

Questions to consider:

Do pupils re-read texts, starting from the earliest stages of reading?

How is pupils’ fluency developed once they have finished the phonics programme? How is this continued throughout the key stages?

How often do pupils have opportunity to read aloud?

Do teachers read aloud daily to the pupils? Is expression and intonation modelled?

Are strategies such as echo reading and choral reading used?

PUPILS WHO NEED THE MOST SUPPORT

“It is likely that pupils with a reading age (RA) of 8 or below will need the support of an SSP programme, though few will need to start at the beginning and pupils with RAs of 8 and 9, are likely to need support in developing their reading speed and fluency”

There is now an extensive section of the framework on how to support older pupils who are struggling with their reading. Reiterating the advice from ‘Now the Whole School is Reading: Supporting Struggling Readers in Secondary School.’, the framework outlines the following:

- Individual assessment should identify any pupils in need of extra support as soon as they begin to fall behind their peers

- Begin with phonics interventions from the highest point possible for the child, taught by staff trained in the school’s chosen SSP programme

- In KS2 and KS3, it is important to identify whether pupils need support either in decoding, fluent word reading or both.

- To support pupils’ comprehension, teachers need to build both pupils’ knowledge of words and the ideas that they represent.

Questions to consider:

Is helping pupils to catch up in reading a priority at your school?

Which assessment procedures do you have in place for reading?

For pupils in KS2 upwards, how do you determine the particular aspect of reading a child is struggling with?

How does the support you put in place enable pupils who have fallen behind to make accelerated progress?

ORGANISING AND PROMOTING BOOKS

“Limiting pupils to choosing unfamiliar books from a narrow level or colour band might not inspire them to read widely and often, and therefore this does not develop sufficiently their ability to read fluently and confidently.”

The importance of phonetically decodable books, linked to a child’s phonics level, is emphasised throughout the framework. In addition to this, there is now guidance for helping choose high-quality, inspiring books for children once they can decode, in order for them to develop their fluency. Picture books, graphic novels, page-turners, and a range of classic and contemporary literature are all recommended additions to text collections. All children should be able to see themselves reflected in books, as well as reading about people whose social and cultural backgrounds differ from their own. The framework encourages practitioners to view school libraries as bookshops and classroom reading areas as mini-bookshops; making these appealing and inviting to the children is key. Remember – your school’s local library is an excellent tool to use in sourcing and promoting books and our Lead Practitioners at One Education can help you select and consider books to suit the needs of all learners.

Questions to consider:

Are book areas high-quality, accessible, owned and loved by pupils?

Are non-fiction and poetry valued alongside fiction?

Do texts broaden the pupils’ knowledge about the world around them, including other cultures?

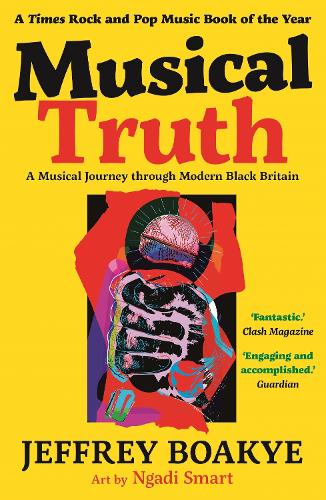

Do pupils have access to contemporary and classic literature, by a broad and diverse range of authors?

Has your school made links with a local library?

READING FOR PLEASURE

“It is impossible to mandate that pupils read for pleasure, but teachers can inspire pupils and engage them in reading widely.”

Once children are fluent readers, it opens the door for them to be immersed in books. Carefully chosen texts that reflect children’s interests and help them to be emotionally invested in the characters are fundamental in encouraging a love of reading. Acknowledging that reading aloud to parents or carers lessens as pupils reach KS2, it is vital that schools give children these rich reading experiences; being read aloud to, participating in book talk, visiting libraries, and making recommendations to peers. Book club (perhaps known as ‘story time’ or ‘library time’) serves as a dedicated time to read, share and discuss a wealth of texts. Giving children elements of choice and making recommendations based on their own preferences will help engage them with reading. Be wary of rewards for reading: aim for all pupils to have an intrinsic motivation to read through a love of books that we, as practitioners, can encourage.

Questions to consider:

Are there opportunities for pupils to read for pleasure on a regular basis?

Do teachers have a good knowledge of current and classic children’s literature?

Do pupils and staff see themselves as readers, discussing their preferences and opinions?

Are pupils given a choice in what they read? Do teachers and peers make recommendations?

Is there excitement built around reading?

READING ACROSS THE CURRICULUM

“Pupils who cannot read well need urgent support. It is vital that all teachers know who these pupils are and how they can provide extra support in the lesson until they can read”

Reading and learning across the curriculum are interlinked; pupils need background knowledge and vocabulary to comprehend what they are reading, whilst they need to be able to read fluently to further their subject knowledge through texts. Have a look at our previous blogs on our One Education Reading Gems to see how this can be woven into your curriculum. Texts chosen in each subject should be age-appropriate in their interest level, with the primary purpose of extending the pupils’ knowledge through reading. Again, activating background knowledge and pre-teaching or discussing any new vocabulary is key for pupils to access the text. Teachers should model decoding any challenging words and provide opportunities for pupils to read aloud through partner or choral work. The use of teacher questioning is key in prompting discussion and understanding a text. Throughout this process, teachers should be aware of which children need support with reading and make these pupils a focus.

Questions to consider:

Do subject leaders help choose high-quality texts linked to their curriculum area?

Do children gain knowledge through reading?

What support is put in place to help less confident readers in subjects other than English?

Are pupils given opportunities to read aloud across the curriculum?

TEACHING READING

“Reading lessons need to create readers, not just pupils who can read.”

The main takeaway from this section is the importance of children being absorbed in texts as a whole, rather than feature-spotting or discussing individual components. Once pupils can decode well, they can be “introduced to a wealth of literature and non-fiction”, which allows them to “think deeply and discuss a range of rich and challenging texts”. Exploring texts is a window through which children can develop empathy skills, a sense of wonder and encounter new concepts and ideas.

As comprehension is an outcome rather than a skill to practise, the framework describes the idea of children constructing a ‘mental model’ of a text through all the aspects of reading coming together. Skilled readers, usually unconsciously, use the following comprehension strategies to access a text: activating and using background knowledge; generating and asking questions; making predictions; visualising; monitoring comprehension; summarising. It is therefore recommended that teachers model and facilitate each of these within reading lessons until it becomes automatic for the children.

Texts used in reading lessons can be more challenging than pupils might be able to access independently, as the teacher guides children through the text. In addition to extracts, poems and short non-fiction pieces, children should be given opportunity to read and enjoy whole texts through the reading curriculum, which includes listening to teachers reading the class novel aloud. We are privileged enough to work with many schools who put reading for pleasure at the heart of what they do in schools as they know and have seen the impact that being able to read, and wanting to read, can have!

Questions to consider:

Are texts chosen in reading lessons challenging and engaging for the pupils?

Are pupils encouraged to think deeply about a text; exploring themes, content and characters?

Is there sufficient focus on background knowledge and vocabulary?

Is there chance for pupils to read complete texts rather than extracts?

Do teachers explain, model and support decoding, fluency and understanding of a text?

Does teacher questioning enable pupils to become skilled readers?

LEADING READING

“Headteachers and senior staff in primary and secondary schools are required to] believe that all pupils can learn to read, regardless of their background, needs, abilities and age, and be determined to make this happen.”

A reading culture starts with the Headteacher and Leaders, and needs to be consistent across classes, staff and stakeholders. The Framework emphasises the importance of “building a team of expert teachers, who fully understand the processes that underpin learning to read”. Headteachers and Literacy Leaders are responsible for overseeing the implementation of a rigorous SSP programme, and any necessary interventions for pupils who are falling behind. Consider if there is someone who is dedicated to ensuring how reading is prioritised and celebrated in your school; through your displays, reading environments, curriculum, books, experiences and extra-curricular activities. You should also consider opportunities for CPD in reading for pleasure – perhaps visiting a bookshop with staff or spending time familiarising yourselves with children’s literature and new releases. The expert teachers are there to inspire staff, children and communities to develop a culture that excites, motivates and engages all in the magic of reading.

Questions to consider:

Is reading a priority throughout the whole school?

Are there high aspirations in reading for all children?

Is there a dedicated Reading Lead? Who leads Phonics? Are they experienced and knowledgeable in the school’s chosen SSP programme?

Are pupils, parents, staff and stakeholders all aware of the importance of reading and its benefits?

Do staff receive regular CPD to help them become experts in reading?

SUPPORTING READING IN KS3

“The transition from primary to secondary school is an important step in pupils’ reading development, as well as ‘one of the most difficult [periods] in pupils’ educational careers’, one of vulnerability and challenge, especially for struggling readers.”

The move from KS2 to KS3 is an important part in a child’s life and the changes in the reading curriculum means that children are expected to be confident in reading to actively engage with more complex, subject specific texts. When pupils start Year 7, it is important to identify which pupils who need support with their reading and who, as a result, have a negative attitude towards school. Once pupils have been identified, they need immediate support which should be across all lessons. Secondary teachers should understand how early reading is taught, as well as systematic synthetic phonics. With this support put in place early on, pupils have the best possible chance to fly with their reading and, in turn, their learning in all subjects.

To help with transition to KS3, especially around reading, schools may want to explore our One Education Transition Pack, which has been written to help bridge the gap between KS2 and 3. Please contact us for more information.

Questions to consider:

Are all secondary school staff aware of the pupils who find reading more challenging than their peers?

Do teachers know how best to support these pupils?

Have secondary staff received training on how pupils develop their ability to decode and comprehend a text?

How is pupils’ fluency developed in KS3?

Do pupils have access to engaging and diverse texts to capture their interest?

Though the Reading Framework isn’t statutory, the DfE guidance does put further emphasis on how important being able to read, and wanting to read, is. For us, anything that promotes the power of reading can only be viewed as a positive. After all, “Reading is the gateway for children that makes all other learning possible.” – Barack Obama.

If you are reviewing your reading curriculum and have questions, or feel you would benefit from some support, please take a look at our One Education website or contact our school development team by emailing: catherine.delaney@oneeducation.co.uk

You may also be interested in working towards our Reading Award, which celebrates the strengths of your reading provision and provides structured guidance for areas of development. For further information please contact us or visit: